Attention Matters - Attention to advertising is declining

The proliferation of media, especially always on mobile technology, means there are more times and places where we can capture consumers’ attention. To put these changes into a real-world context, it’s worth knowing that android sends out 11 billion notifications per day, and on average, consumers check their phone 150 times per day for short bursts of 30 seconds.

This should mean our job is getting easier. But all the signs are that attention to advertising is in decline. A recent report from Teixeira shows a steep decline in the number of adverts viewed. In the online environment viewability is widely acknowledged as a significant challenge, and a viewable advert doesn’t necessarily mean the consumer has paid attention to the advert. Furthermore, the rise of adblocking software means that all these opportunities that are being opened up to reach the consumer are compromised.

TGI data tells a similar story about attitudes to advertising, with 51 percent of consumers agreeing that they feel bombarded by advertising, this up from 45 percent in 2015. Recently, a study from the

Advertising Association think tank Credos, showed that public favourability towards advertising hit a record low of 25 percent in December 2018. According to Credos, shis was the latest measure in a "long-term decline" in trust in advertising.

There is an inherent contradiction in attention. As Herb Simon explains, there is an inverse relationship between the availability of information and attention. Increased information results in a scarcity of attention. This means that attention has become a precious commodity in our content rich world.

The media industry is focused on reach and interruptive attention

The digitalisation of content and distribution has made attention cheaper and easier to capture, and the abundance of data has enabled optimisation. This has resulted in a reach led approach to attention, focused on interruptive strategies, grabbing attention and maximising eyeballs.

The reality is however, that attention is a finite resource. Put simply there are only so many hours in the day. Attention strategies that are based on the premise of interruption, capitalising on low quality attention and maximising reach could prove problematic for the long-term health of advertising. Attempting to squeeze more and more attention out of increasingly distracted consumers risks undermining our overall capacity for attention to advertising.

Communication strategists such as Oliver Feldwick and Faris Yakob have questioned the sustainability of an attention-grabbing approach. So how do we achieve a more sustainable approach?

Achieving a sustainable approach to attention

The starting point is an appreciation that not all attention is equal, and that we need to place greater emphasis on quality attention. Quality attention is not just clicks, it can’t be measured in eyeballs alone, it’s about time well spent, it’s about focused and immersive attention. Yacob asks us to consider a spectrum of attention, to acknowledge for example that the requisite two seconds online hoping to attract a thumb is very different to watching a 30 second commercial in a darkened movie theatre.

So instead of grabbing attention, we need to think about cultivating attention over the long term; this is a more sustainable approach. This means prioritising an approach that values meaningful media experiences, where advertising isn’t interruptive and ad avoidance is low.

How to measure attention

The challenge, as always, comes back to measurement. Whilst it’s relatively straightforward to make an intellectual argument for quality attention, advertisers will inevitably want to be able to quantify ‘quality attention’. The difficulty here is that with a mix of complex and subtly different metrics, it is incredibly hard to compare attention across different platforms.

Time spent is one of the standard ways to measure attention, unfortunately it’s not as simple as that. A recent report from Ipsos MORI and Lumen acknowledges that, even in the online environment where dwell time is a standard metric, this doesn’t provide the full picture. Analysis of creative performance of digital ads found that a well created digital advert can deliver recognition at a glance and aid brand impact. When a weaker ad might not perform even with a longer dwell time.

In our ‘Attention Please’ whitepaper in collaboration with Bournemouth University, we outlined the need to consider intensity of attention; this refers to a more qualitative understanding of attention.

There are different types of attention

With this in mind, Bournemouth University developed a framework for understanding attention, which acknowl- edges there are different types. Informed by a variety of theories, they assert that attention sits on a spectrum from top down, which is conscious and immersive, to bottom up, which is unconscious and fast.

Alongside this we also need to consider how people process information. Information can be processed cognitively, i.e. analytically based on supporting arguments, often text based or lists of attributes or features. Or they can be processed emotionally based on value expressive goals linked to self identity. Typically these are more reliant on imagery and seek to meets moods, desires and feelings.

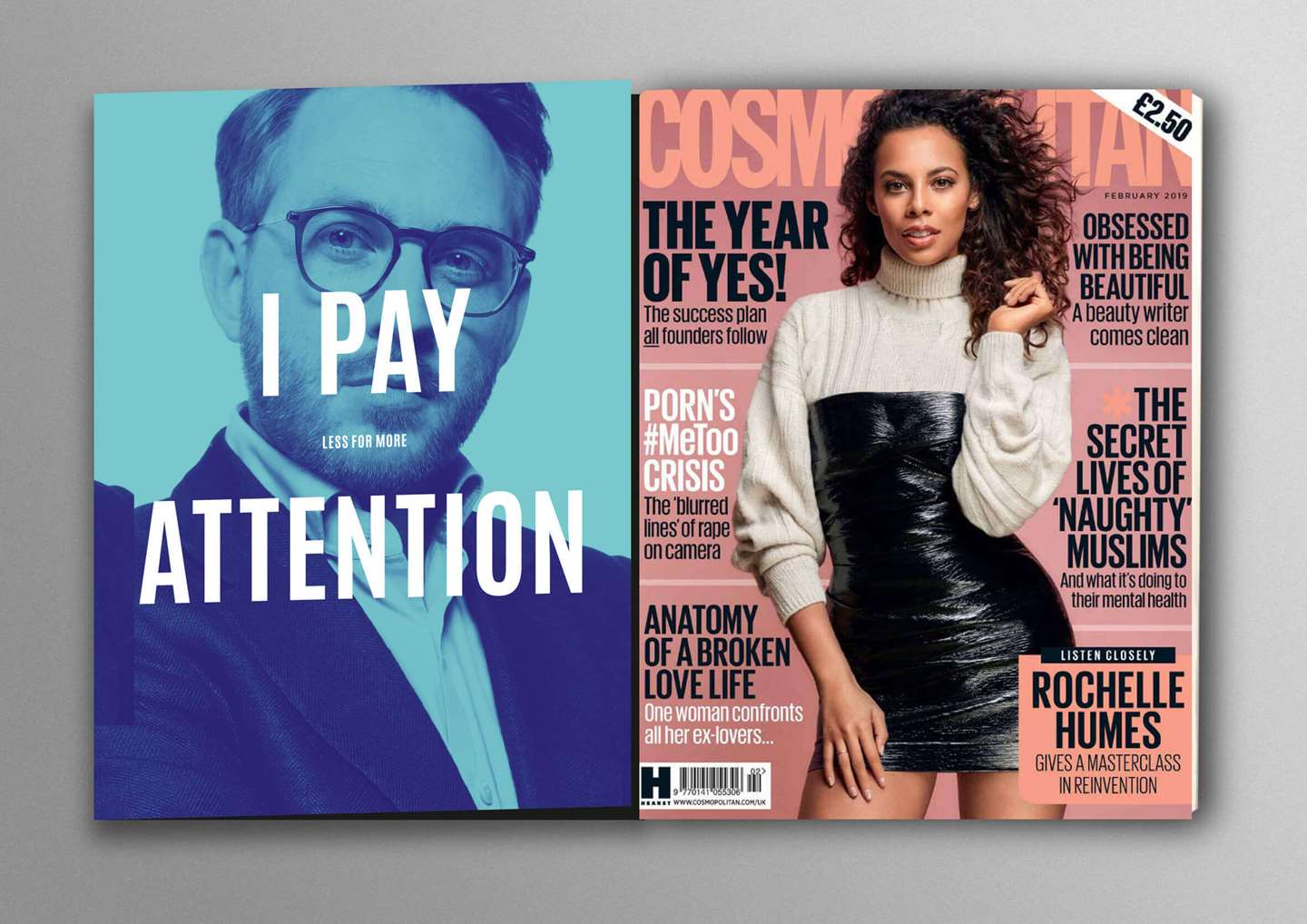

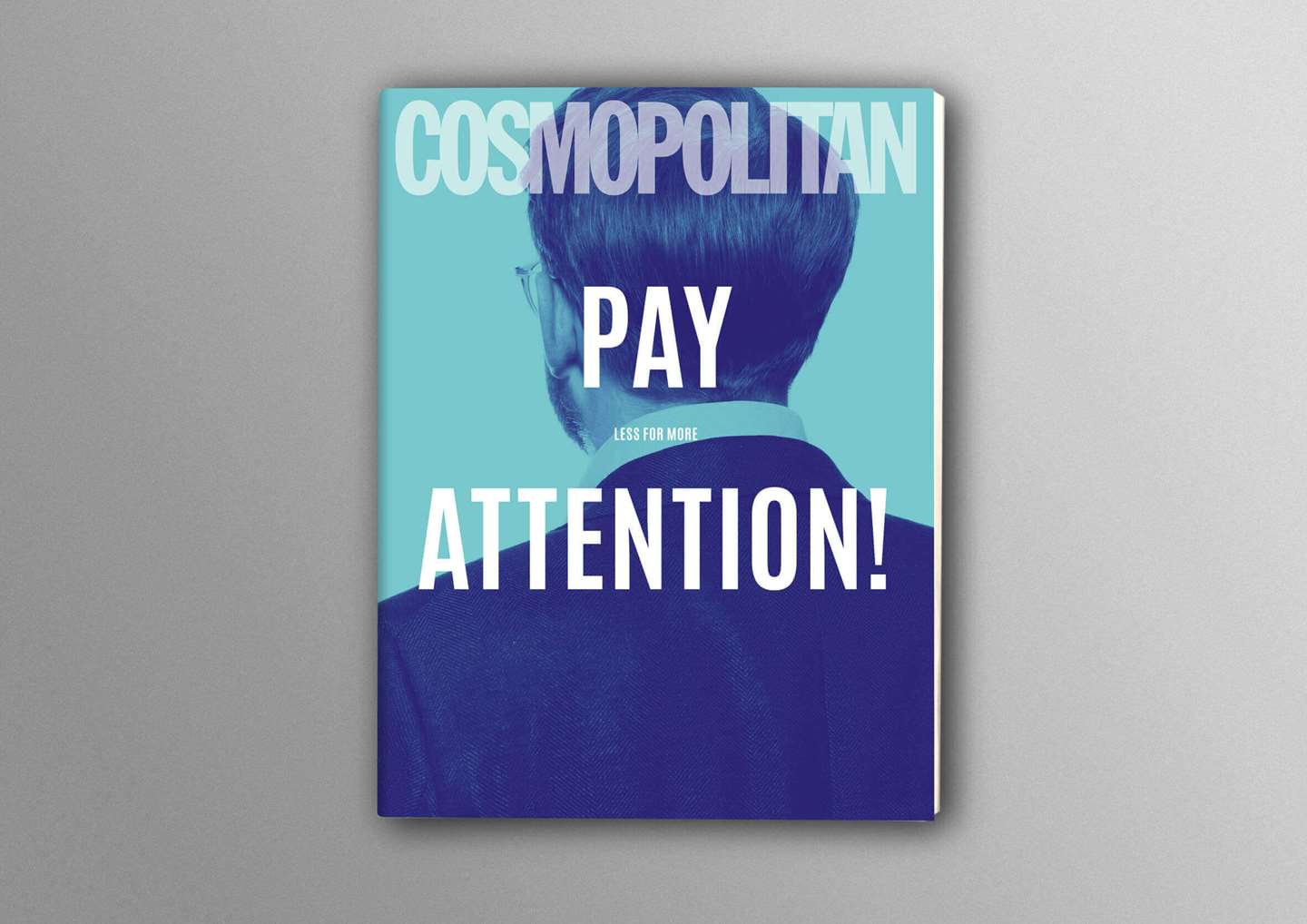

It can be argued that different objectives and sectors are better suited to different types of attention, so it’s important to consider this when planning a campaign. A useful way to think about this is the idea that attention has different modes: studying, soaking up, skimming and scanning. You might select one of these on the basis of the creative you are working with, the message that you are trying to communicate or the behaviour you are trying to change. Advertisers can use any or all of these modes depending on their objectives. For example, the above Smart Energy campaign used all four modes deploying cinema and advertorials in magazines for top down immersive attention and display advertising and video online to achieve bottom up interruptive attention.

Media channels don’t naturally sit in one mode or another; many straddle a number of modes depending on how the channel is deployed and the creative treatment. A magazine for example, can be studied, soaked up or skimmed depending on the title, whether the consumer is reading in print on, social or online, and the creative approach taken with the commercial message. For example, a display advert, a partnership strategy, a home page take-over or an online influencer campaign.

From this framework, the important take out is to work with the type of attention that your brand objectives, creative and media channels are best suited to. This is the best way to achieve a higher quality of attention.

Quality attention drives actions

Measuring attention is undeniably a challenge. A single metric is unlikely to fully account for the different types of attention and all the variety of factors that influence it. In our ‘Attention Please’ whitepaper Bournemouth university highlighted five contextual factors that need to be considered when measuring attention.

a) Advertising goals: Purpose of the advertisement (desired outcome, remind, inform, change attitude, build brand etc).

b) Personal goals: Utilitarian or value expressive (and specific nature of those goals).

c) Media moment: how the media is being experienced (escapism, diversion, killing time).

d) Media brand/channel relationship: Consumers’ relationship with particular media brands (pleasure, purpose, trust, relevance, credibility, personal connection, emotion, control, personal choice, loyalty).

e) Advertising relationship: Consumers’ relationship with an advertisement (part of experience, relevance, distracting, annoying etc).

So is all this complexity worth our attention because ultimately the measure of success in advertising comes back to proving effective outcomes. For attention to be taken seriously as a topic, there needs to be a link between attention and important KPIs, such as purchase and consideration.

Neuroscience provides some compel- ling insight into this question. In this field, attention is referred to as memory encoding, and memory encoding is seen to be a crucial metric. The science shows that if something isn’t stored into memory, no matter how much we enjoy it at the time, it can’t possibly affect our future behaviour – if it’s not stored away into memory, it’s simply not there in our heads.

The significance of memory goes even deeper than this, because our brains are very selective about what is stored away, and we tend to encode things for which the brain has already identified a use. Therefore if something is encoded into memory, this is both an enabler and predictor of likely future behaviour.

In neuroscience, we find that attention really matters because the ultimate goal of any campaign is always to create some kind of behaviour change.